The 3rd Generation Ford Mustang

1979 – 1993

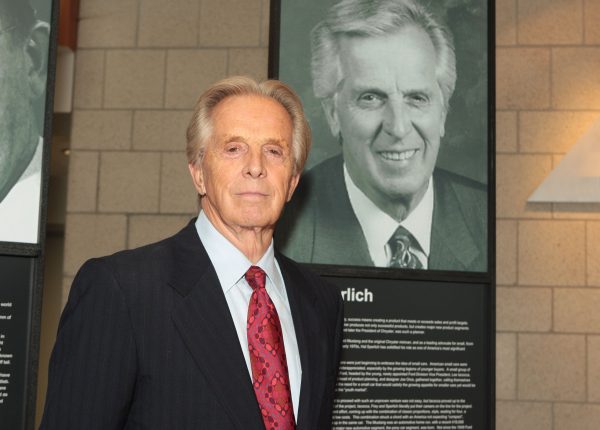

The Ford Motor Company made two significant changes in 1978. The first is that, under the direction of Henry Ford, saw the termination of Lee Iacocca from the Ford Motor Company. The second is that it saw the discontinuation of the short-lived Mustang II.

Despite some conjecture among the Mustang community, Iacocca was not fired as a bi-product of the poorly received Mustang II. Ford parted company with Iacocca because he’d outgrown his position. According to a public statement by Henry Ford II, he let Iacocca go “for insubordination.” There are other conjecturers out there who suggest that Henry II had simply grown to dislike Iacocca, and some even believe that he’d grown jealous of Iacocca’s marketing genius.

Whatever the reason, the departure of Iacocca marked a significant milestone in the history of the Ford Mustang. Afterall, Iacocca had been the visionary behind the car’s creation and had been almost solely responsible for nearly every iteration of the Mustang in the history of the brand (save for the Boss Mustangs which were developed by Buckie Knudsen and sold between 1969 and 1971 and, of course, the Shelby Mustangs, though the latter was an aggressively souped-up version of Iacocca’s Mustang.)

Lido (“Lee”) Anthony Iacocca was fired from Ford in July 13, 1978, about the same time that the 1978 Ford Mustang II completed production. By November 1978, Iacocca had found his way to the Chrysler Corporation and immediately set to resurrecting the car company from almost certain bankruptcy. While Iacocca was instrumental in saving Chrysler, thanks in large part to his introduction of the Dodge Caravan/Plymouth Voyager (both of which had more than a passing resemblance to a Ford-designed minivan prototype that Iacocca had overseen a decade earlier), he was also responsible for the continuation of the Ford Mustang program as it moved past the Mustang II era and into the Fox-chassis generation.

Evolution of the Fox-Body Mustang

The evolution of the Fox-body Mustang dates back more than a half-decade before the car’s official introduction late in 1978 (as a 1979 model-year Mustang).

First, the evolution of the pony-car into a compact automobile began in 1972, as Ford finally started to recognize the financial impact that imported automobiles was having on the U.S. automotive marketplace. Ford’s response to this realization was largely what led to the creation of the Mustang II.

However, while the Mustang II provided a viable Ford-built alternative to consumers, Ford’s engineering division was looking beyond the Mustang II and was instead trying to realize a full line of small-to-mid-size automobiles all based on a similar chassis platform known as the “Fox Chassis.”

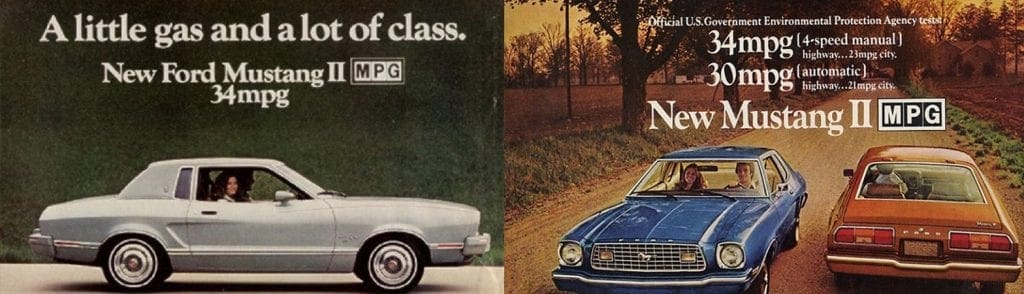

In 1973, the American automotive industry was forced to undergo a sort of metamorphosis. In May of that year, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its first comprehensive list of fuel economy data. Although commonplace today, this reporting gave consumers their first critical analysis of vehicle fuel consumption. It was also used to establish Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) protocols as well as separate protocols for gas-guzzler taxes.

For the first time, American consumers were actively monitoring fuel economy.

Then, in October 1973, the Arab oil embargo created one of the first, major oil crises in the United States. Almost overnight, American consumers saw gas prices increase some 55 cents per gallon. As fuel prices rose, so too did the sales of small, fuel-efficient import automobiles. Where import sales in the U.S. had accounted for roughly 10 percent of all automobiles sold before 1973, that number increased to approximately 15 percent by 1975-76 and rose to nearly 23 percent by 1979.

Whether Ford’s engineers may have had the insight (or just plain, dumb luck) to foresee the inevitability of downsizing their vehicles to improve on fuel economy, rising gas prices (and scarcity of petroleum) now forced them to accelerate their downsizing measures and to continue to look more broadly at all of Ford’s offerings, beginning with the Ford Granda in 1975 and continuing with the new Fairmont in 1978.

About the time that the Arab oil embargo was most heavily impacting the oil reserves in the United States, then Ford president Lee Iacocca and chairman/CEO Henry Ford II had decided that changes needed to be made at the executive levels of the Ford Motor Company.

William O. Bourke, ex-chairman of Ford in Europe (as well as one-time director of Ford of Australia), was promoted to Executive Vice-President of North American Operations. Additionally, Rober Alexander, who had previously worked as Vice President In Charge of Car Development with Ford in Europe was moved to that same role within the United States. Additionally, Hal Sperlich now served as Ford Vice President of Product Planning and Research.

Sperlich’s involvement with the next-generation Mustang was as much a bi-product of Ford’s desire to develop a single, broader product offering that could be sold globally as it was a product of downsizing. In an effort to meet the design expectation put forth by Ford’s top brass, Sperlich conceived of a “World Car” that could be sold globally, regardless of the market into which it was introduced.

In December 1973, Lee Iacocca formally approved Sperlich’s “World Car” concept as well as the formal development of the Fox platform.

As an interesting sidenote, Hal Sperlich is credited with keeping Mustang development costs low by using Ford’s existing Falcon chassis. In fact, some consider him to be the “true father of the Ford Mustang.” Sperlich was an early advocate of efficiency and smaller car design, which was represented directly in the development choices made both in earlier iterations of the Mustang and most especially, in the “World Car/Fox Body” Mustang. Sperlich was fired by Lee Iacocca under orders from Henry Ford II, who found Sperlich too pushy and argumentative. He later joined the Chrysler corporation and teamed up with Lee Iacocca again to create another wildly successful vehicle of a very different sort — the Chrysler Minivan.

Interestingly, the Fox platform evolved from a popular European subcompact automobile known as the Audi Fox (although the “Fox” name was not specifically lifted from the Audi model.) Ford executives recognized that the Audi Fox had set a benchmark in new design and had garnered immense popularity from its European fanbase.

Inspired by the Audi Fox, Ford Engineers elected to take a wider approach to downsizing many of the models in the company’s current production lines. Development of several shorter-wheelbase Ford automobiles started in late 1973 thru 1974 with models including the Pinto, Cortina and the Taurus. However, it was the Ford Fairmont (and its Mercury Zephyr counterpart) that would become the first Fox-based car to reach the marketplace.

At the same time, there were more than a few passing rumors within Ford that a new and highly-anticipated sports coupe would also be developed using the Fox platform. In October 1974, those rumors were confirmed. Ford announced that a Fox-based Mustang chassis would be developed to replace the Mustang II.

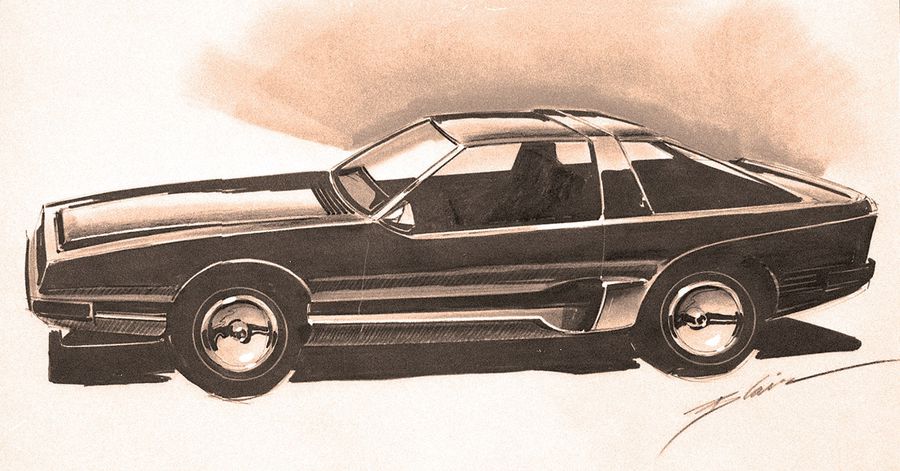

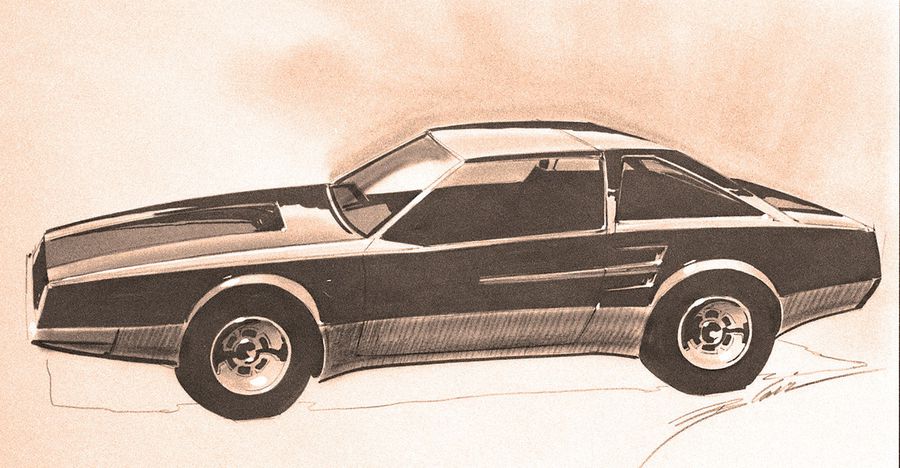

Design work on the new Fox-Body Mustang began in earnest in July 1975. The team behind the new Mustang – which included much of the North American Automobiles Operations division – took over the development of the Fox platform from Sperlch’s product planning and research group.

The new Fox Mustang was visualized as a notchback automobile with a sloping roofline from the start. Aerodynamics, which had gained popularity as an emerging science within automotive circles during that time, became especially important to the new Fox-Body Mustang’s design. Engineers working to streamline the new Mustang’s form reasoned that the new car didn’t need to be smaller to be fuel-efficient. Instead, it could save on gas by “cheating the wind.”

Considerable effort went into developing a cockpit that offered drivers more room than had been made available in the current Mustang II. At the same time, a great deal of thought went into weight-saving measures that would actually lighten the new Mustang. This was accomplished thru the careful selection of materials that were to be incorporated into the car’s cockpit.

As its fully realized design began to take shape, the new Fox-Body Mustang did indeed offer consumers considerably more interior than the outgoing Mustang II. This new Mustang’s cockpit was longer, taller, and easier on passengers’ legs than its predecessor despite an outward appearance that suggested the new Mustang was actually shorter (and by a fair amount) than the outgoing model. More than that, the third-generation pony car would actually weigh 200 pounds less than the Mustang II, thanks in large part to the car’s urethane bumpers, soft front fascia, and thinner doors and windows.

With the basic design parameters sorted out, the Fox-body styling process was turned over to Jack Telnack, then former European Design Vice President of the Ford Motor Company. Now relocated back to Dearborn, it was Telnack that became Ford’s North American Light Car and Truck Design executive director in April 1975.

Almost from the start, Telnack had a specific vision for the next-generation Mustang. While he contracted a number of studios to provide conceptual designs, it was Telnack’s own team that eventually developed the look of the Fox-body Mustang that won over Lee Iacocca as well as much of Ford’s top brass. By late 1975, Telnack’s vision for the new Mustang was widely embraced by Ford. In fact, the conceptual designs that Telnack introduced remained virtually unchanged through its entire development phase and up until September 1976 when Ford gave the car final production approval.

Telnack’s Mustang was a visual work of art. Unlike its Mustang II predecessor, the Fox-body model was sleek, giving way to a form that was as much functional as it was fashionable. This new Mustang fastback was immediately recognized as being one of Detroit’s most aerodynamic automobiles to date. The car had a drag coefficient of just 0.44 which, for its time, was considered an impressive engineering feat. (It should be noted that most production cars built today have a coefficient of drag of 0.25 to 0.30 (on average.))

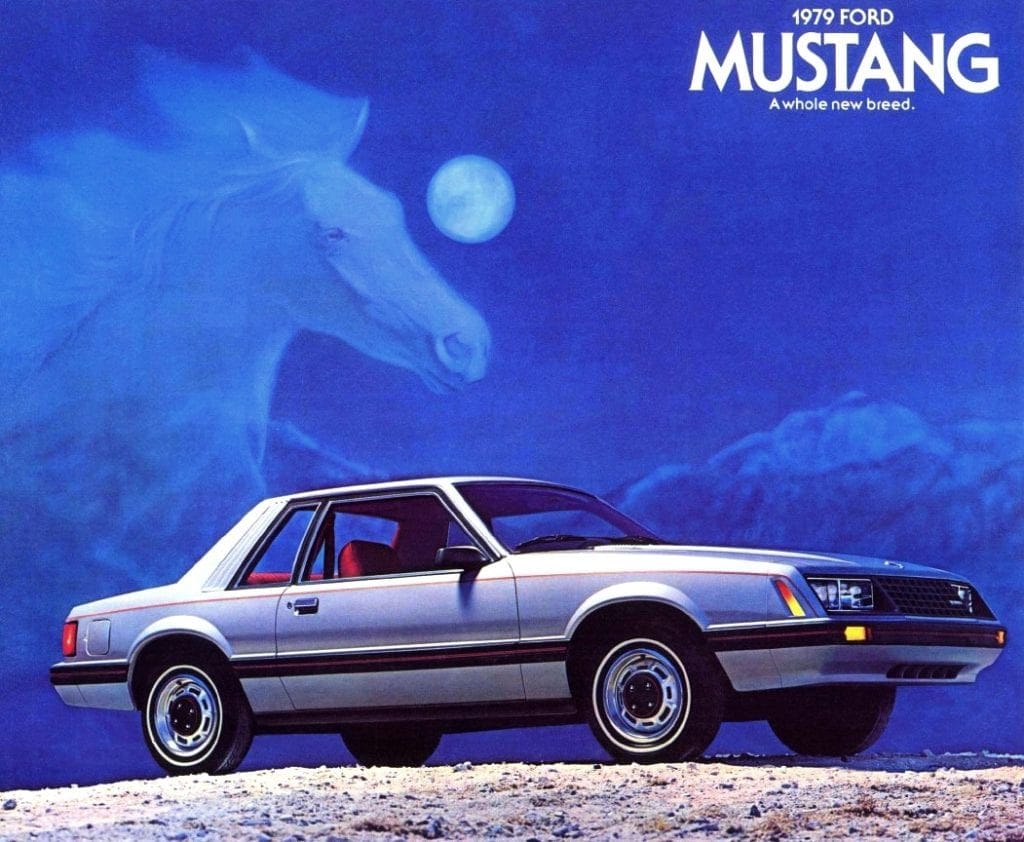

Ford introduced the Fox Body Mustang in the fall of 1978 as a 1979 model year production vehicle. The car, which was offered both as a two-door coupe and a three-door hatchback, was an overnight success among Mustang enthusiasts. Everyone marveled at the car’s aerodynamics and how easily the car moved through the air. Even the coupe, which had a slightly higher (0.46 vs. 0.44) coefficient of drag, was a spectacle to behold.

The base-model Mustangs came equipped with a 2.3-liter, four-cylinder engine topped by a single overhead camshaft. However, Ford once more offered optional powerplants for its newest Mustang, including a turbocharged four-cylinder engine and a larger V8. While this latter offering was rated at a meager 130 horsepower, there was little doubt amongst enthusiasts that Ford was edging its way back to transforming the Mustang into a performance vehicle.

More than the available powerplants, the car’s new chassis (per the Fox chassis specifications) was designed to provide vastly improved handling over the outgoing Mustang II. The car’s front-end now featured MacPherson struts with coil springs wedged between the lower control arms and the subframe instead of being wrapped around the strut towers. Rack and pinion steering was also included as part of the new front-end design.

The car’s back-end now featured coils in place of the more traditional leaf-spring assemblies. Each of these coils were mounted to the rear axle via a four-link assembly. A rear stabilizer bar was also installed to add lateral rigidity during more aggressive cornering.

Per Motor Trend’s John Ethridge, the new Mustang could “now compete both in the marketplace and on the road with lots of cars that used to outclass it.” By the time the new Fox Body Mustang arrived at dealerships across the nation, demand for the car was monumental. In fact, the 1979 Mustang sold just less than twice the numbers that the 1978 Mustang II had the year before – a total of 369,936 units total (compared to 192,410 units the year before.)

NEXT: More research on the Third Generation Mustang